James Tissot's "Life of Christ": The Complete Online Gallery and Introduction.

- Shane Jenkins

- Nov 2, 2020

- 15 min read

Updated: Aug 16, 2023

Seventeen years of consistent labor, three trips to the Middle East, more than 700 paintings and drawings, all by a man who was confidently and paradoxically criticized and praised by every group he inhabited.

James (Jacques) Joseph Tissot (1836-1902) was a successful and renowned painter, recognized for his salon paintings, etchings, and depictions of Parisian and London high society. But at age 50 he abandoned the comfort and legacy he attained in that world and dedicated the rest of his life's labor exclusively to manifesting the message of God's love for humanity. By the time Tissot died in 1902, around 15 years later, he had created what remains to this day the most exhaustive (and potentially the most ambitious) series of paintings ever based upon the Holy Scriptures.

This story is about the devotion of a man who was too British for the French yet too French for the British, too traditional for the Impressionists yet too modern for the Old Masters, too mystical for progressive intellectuals yet too quickly forgotten by his many Christian viewers.

Though Tissot's works have recently become more accessible through the efforts of the Brooklyn Museum and other Tissot scholars, this page hopes to provide the most complete digital collection of the 500+ original works within Tissot's Gospel narrative, combining them into a single, accessible presentation. Though individual pictures of the series are available in various places with various levels of quality, this may be the only complete and high quality presentation since the entire series was last on full display in the early 1900s. Hopefully, by making Tissot's Gospel accessible to the public once again, his original hope for the project may live on: to help the viewer witness Christ's ministry and sacrifice in our world and experience His love from a fresh perspective. I hope that you enjoy this fascinating and expansive devotion which captivated its brilliant creator to his very death.

Link to the gallery for James Tissot's Life of Christ, etc. Introduction to Tissot is further below:

The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ

The Holy Childhood (Slide 3)

The Ministry (Slide 35)

Holy Week (Slide 183)

The Passion (Slide 214)

The Resurrection (Slide 320)

Supplemental Content (Slide 357)

The Old Testament

Full Painting Gallery (Update as of 30 May 2023: I hope to complete this, but I have been delayed due to a busyier phase of life. Let me know if this is something you would enjoy seeing!)

Jacques or James, which is it?

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in Nantes, France on the 15th of October 1836 to Marcel Théodore Tissot and Marie Durand, a drapery merchant and hat designer respectively. Ostensibly drawn to British culture from a young age, Tissot chose to anglicize his first name to "James" at about the age of 18. Soon after in around 1856-7, Tissot traveled to Paris to pursue education in one of France's most established academies of art, the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). He studied under salon-style masters, such as Louis Lamothe and Hippolyte Flandrin, at the same time growing close to his painting peers: the soon-to-be-famous figures of James Whistler, Éduoard Manet and especially Edgar Degas. (Paquette, "A James Tissot Chronology")

Success in both Paris and London

Finding success in the early stages of his career, Tissot exhibited various paintings in the Paris Salon which provided him with considerable recognition and financial support. Soon after, however, the Franco-Prussian war and the rise of the French Commune interrupted his life. Tissot joined the fight to defend his city alongside the Paris Commune–a socialist, progressive, and anti-religious political movement–though there was some doubt as to whether this decision suggested any political sympathy from Tissot or simply an eye for self-preservation. In the aftermath of this war, Tissot fled–or possibly just left for greater opportunities–to London in 1871 and pursued his profession in the more stable environment, starting over with hardly a penny in his pocket.

It was during this portion of Tissot's life, however, that he gradually achieved his enormous wealth and widespread notoriety. Contrasting this financial success were many British critics who asserted that Tissot's works were underwhelming, simply soaked in typical French style and character. Even Tissot's artistic peers began to describe his success, extravagant lifestyle, and expensive commissions as far too inflated for Tissot's actual worth. Nonetheless, Tissot spent much of this time painting scenes from aristocratic gatherings, experimenting with etchings, and even performing some illustration work, such as providing Vanity Fair with many iconic caricatures under the pseudonym of Coïdé. In 1874, Tissot was invited by his old friend Edgar Degas to contribute to an impromptu exhibition back in Paris. This alternative exhibition would soon be recognized as the first major gathering of the painters known as The Impressionists, a historic opportunity to be sure. Tissot, however, apparently declined the invitation and continued his work in London, but he remained in contact with his peers all the same.

Ms. Kathleen Newton

For a brief, but emotionally dense, portion of Tissot's life from 1876-1882, he met and eventually share a home with the young divorcée Kathleen Newton. A woman of Irish Catholic heritage who grew up in the south Asian colonies, Newton met Tissot soon after divorcing her British husband and moving to London. Tissot was evidently moved by Newton and after the two became further acquainted he invited Kathleen and her children to come live with him at Grove End Road. This broken family's influence upon Tissot is immediately evident in the changes to the tone and character of his subsequent paintings. He began to focus less on scenes of parties, high class drama, and busy cosmopolitan life, and instead moved toward pictures of tranquillity, family life, and domesticity, often using Newton and her children for his subjects. Unfortunately, this contented portion of Tissot and Newton's life as a 'family' soon came to an end when Newton succumbed to a long struggle with consumption (tuberculosis) in 1882. Newton's death left a visible mark on Tissot, who for many years after would dabble with mysticism and mediums, seeking to make contact with the deceased Newton. One of Tissot's paintings, The Apparition, whose original was thought to be lost or destroyed until a mere two years ago, portrays Tissot's vision from one of these sessions: Kathleen Newton next to the famous medium William Eglington (Carrigan).

Immediately following Newton's death, Tissot re-fled from London back to Paris and took up work at a new studio. He worked on a few different projects including The Prodigal Son in Modern Life (a subject he had already depicted in the context of the Middle Ages during his salon years) and the massive portraits of the La Femme à Paris series (The Woman of Paris). Both of these projects were again received with mixed praise and criticism. This time around though the French critics highlighted the overwhelming British influence which they felt masked Tissot's French character (Paquette, "Tissot’s La Femme à Paris series").

A Movement of the Spirit

Halfway through the process of the La Femme à Paris project, Tissot began working at the Church of Saint-Sulpice to research the next piece, La Femme qui Chant dans l'Église or Musique Sacrée (The Choir Singer or Sacred Music). Accounts of the experience which followed vary slightly and were sometimes influenced by gossip or the feelings of the person doing the retelling. But overall most report that Tissot paused from his work when a priest began to celebrate mass. Having been raised with the habits and respectfulness of his devout, Catholic mother, though not a practicing Catholic himself, Tissot knelt at the beginning of the Eucharistic prayer. Then, when the priest raised the host for consecration, Tissot felt seized by a vision of two homeless peasants resting within the crumbled ruins of a once great building–possibly the ruins of the French state (Dolkhart, 32 note 2). Then he noticed that leaning on their shoulder, but unknown to the couple, was a wounded and scarred Jesus. He bore a crown of thorns and the other signs of his passion but most importantly was consoling them by joining them in their sorrow [(Muchmore), (Bailey, 473), and (Dolkhart, 11)].

Tissot felt so plagued by this vision that he abandoned his Woman of Paris project and discreetly painted this intimate scene in the work Inward Voices (The Ruins).

Creating The Life of our Saviour Jesus Christ

Deeply moved by this whole experience and perhaps still suffering from the loss of Kathleen Newton, Tissot dedicated almost the entirety of his remaining life to creating subjects of a Christian nature. Starting only with the intention to depict a few scenes from the Gospels, he ventured to Egypt and Palestine for the first time and lived as a pilgrim for many months. He hoped to experience the events of the Scriptures in their native setting and to capture a lost vision of the Holy Land. Soon enough, Tissot would decide to expand his project, return a second time, and paint the entirety of the Gospel narrative as a single, cohesive story.

As Tissot suddenly disappeared from his refined and artistic circles, rumors began to abound. Many speculated that Tissot had left the city to live out a religious life in a monastery. Others believed that his sudden conversion and absence were merely part of a sensational act, capitalizing upon and profiting off of the Catholic revival movement emerging in France at the time. Even long-time friend Edgar Degas turned his back on Tissot, so much so that their friendship would never be repaired. He is quoted as saying, "Now he's got religion. He says he experiences inconceivable joy in his faith. At the same time he not only sells his own products high but sells his friends' pictures as well.… Well, I can take my vengeance. I shall do a caricature of Tissot with Christ behind him, whipping him, and call it: Christ Driving His Merchant from the Temple…" (Wentworth, 190). Far away from the rumors, however, Tissot marched toward Jerusalem, accompanied by no European friends–only local guides, interpreters, and assistants to aid him.

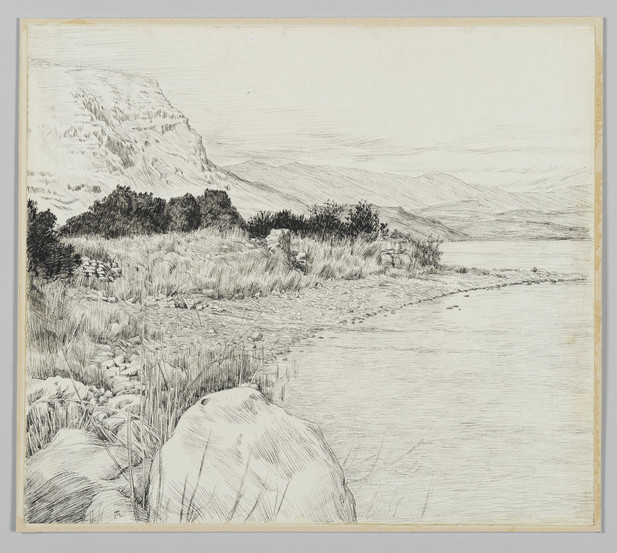

In total, Tissot took two long trips to the Holy Land in 1886-7 and 1889 where he assembled sketches, pen drawings, photographs, and character models for his project. Later interviews and accounts of his journeys reveal that Tissot approached his first trip to the Holy Land with great intentionality (Moffett). Upon his first approach toward Jerusalem he resisted his guide's advice to enter the city by the gate of Jaffa (the most direct path) to avoid the coming rain. Instead, Tissot insisted that the luggage be sent ahead while he made an hour long detour to approach the city from Mount Scopus. He did so while shielding his eyes, lest he see the city for the first time before reaching the perfect vantage. After completing this detour, he saw Jerusalem from the same perspective that Jesus would have. Even then, Tissot felt that he could scarcely sleep until he entered the city and visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Perrin).

After settling into the city, however, Tissot took a strict and almost monastic schedule: 6am to wake, 7am morning prayer with the nuns of the Convent of Marie Reparatrice, a few hours of excursion and work with the aid of his paid assistants, a break for lunch, a few more hours of work inside or outside the city, and then evening came whence he would dine and rest mostly alone, perhaps taking notes or creating sketches for future reference. Tissot's daily research would typically consist of seeking out locations and people for his sketches, speaking with local biblical authorities from both Jewish and Christian sects, and–perhaps the most visually massive task–studying and reconstructing the geography of Jerusalem; this last task meant envisioning how the now-destroyed Jewish Temple would appear within the ancient city and deconstructing the subsequent growth around the hill of Golgotha to reveal the original terrain beneath. For all of this strict work though, Tissot rarely saw it as tedious or overwhelming in proportion. Instead it was exactly what motivated him each day: "'Ce n'était pas un travail, c'était une prière.'–It was not a task, it was a devotion [prayer]." (Moffett)

Many months of this work passed and yet little to no painting would be done while Tissot was in the Middle East. Most of his actual painting would be completed between his studios in Paris and the Chateau de Buillon, a familial estate in the French countryside. Though he relied on photographs, miniature sketches, and lasting memories from the trips, Tissot also humbly credits the visual inspiration he received from prayerfully meditating over each subject. Having only a vague sketch of charcoal lines and ovals before him, Tissot would pray and eventually 'see' the religious event laid out before his eyes–the characters, the clothing, the actions, etc.–and then copy what he saw as best as he could manage [(Moffett) and (Sherard)]. Many of the journalists who reported on Tissot's work admired him for this unique 'hyperesthesia.'

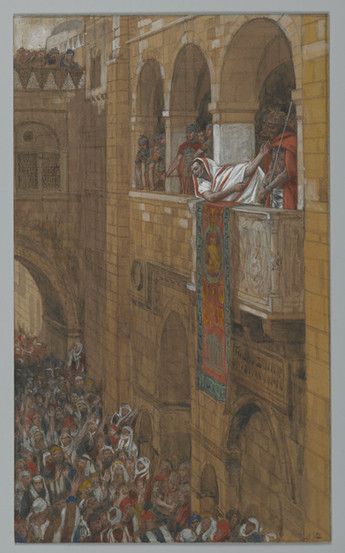

In total, the creation of this project would stretch over ten years, with Tissot working feverishly to complete 500+ compositions at a rate of around one per week. His completed series would reach its grand conclusion in three massively acclaimed exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York, where wealthy men and women were often seen to enter on their feet and eventually end up crawling on their knees as they moved through the narrative across hundreds of paintings. Tissot's series also found immense success in the form of a widely popular synthesized version of the four Gospels that was accompanied by prints of Tissot's paintings, drawings, and historical notes. The more expensive French edition of the Gospel came first, whose publication rights earned Tissot one million francs alone–which is, by my calculations, well over 3.4 million Euro in today's currency (Paquette, “James Tissot: Portraits of the Artist”). The English language edition (known interchangeably as The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ, The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, The Life of Christ, or most vaguely as "Tissot's Bible") became a beloved and accessible piece of instruction Christians across the English-speaking world.

Tissot made a third and final trip to the Middle East in 1896 to begin working on his next project: illustrating scenes from the Old Testament. Though he completed over 100 paintings for this project from 1896-1902, Tissot's labors came to a close when he died suddenly at the Chateau de Buillon in Doubs, France on the 8th of August 1902. In 1904, a book of these final paintings from the Old Testament, similar to The Life of Christ, was published.

Tissot's massive project netted him immense financial reward and expressly positive reviews from the general public. At the same time, however, The Life of Christ series has been harshly critiqued by Tissot's artistic peers, present day art critics, and even the journalists who announced Tissot's death in the papers ("Death of M. James Tissot").

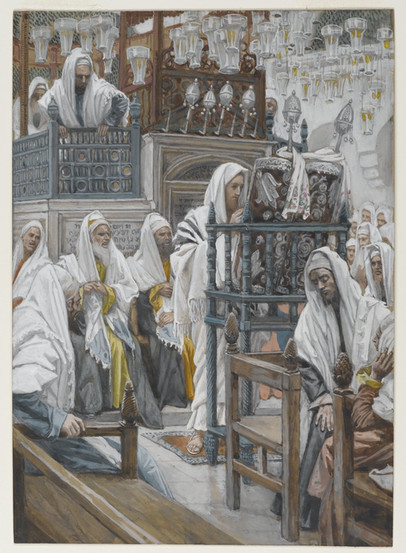

Some of the intellectual artists among the Impressionists and Realists dismissed Tissot's series as "revolting" and mediocrely supernatural (Paquette, "Portrait of the Pilgrim: James Tissot’s Reinvention (1885-1895)"). This criticism seems at least somewhat undeserved as Tissot's approach to the genre of religious painting had consciously broken away from the limitations of past European representations. Tissot saw the former works of the European masters as noble in their intent, but fundamentally limited as they would always be half-blind depictions draped in the clothing and "fancies" of their own homelands (Dolkhart, 17). Furthermore, Tissot's style of conveying the supernatural has become one of the most identifiable and beloved characteristics of the series.

Even contemporary critics and academics still find fault with Tissot's project. For one critic, quoted by Lucy Paquette, Tissot's supernatural elements are mere "spooky illustrations" ("James Tissot, the painter art critics still love to hate: a retrospective review round-up"). The first wave of Tissot historians almost entirely ignored this period of religious artwork, treating it as a trivial indulgence at the end of a great artist's life (Carrigan). Furthermore, for many of the contributors to Shofar, a journal of Jewish Studies, Tissot's work remains intrinsically unapproachable or at least historically inaccurate for presuming that the appearance and dress of people in the Holy Land in the 1890s would look at all like the context of Jesus' time (Garber). Little recognition seems to be given, however, to the the relative difference between Tissot's style and that of almost every western Christian artist before him. (see below for an example of the stylistic change seen in Tissot's treatment of the Nativity on the right, contrasted with the scene painted by Correggio on the left).

Though certainly not immune to all forms of criticism, Tissot sought to create a vision of the Gospels that resembled the world of Jesus's time as closely he could witness it. Modern in his style, attentive to detail, and original in his depictions of previously unrepresented scenes, Tissot embraced the core elements of the Christian artistic and historic traditions, inviting the input of both Jewish and Christian scholars to aid his work, while also desiring that a new, recovered picture of Jesus' life might bring the message of God's mercy and loving sacrifice to the hearts of his audience.

Though Tissot's Life of Christ has almost entirely disappeared from the present day's social memory, its impact upon the western imagination can be felt in the dramatic shift of almost all subsequent depictions of the holy land. In general, the west's perception of biblical Palestine shifted closer to Tissot's semi-historical vision rather than simply dressing the story in western clothes (though this trend has its exceptions and set may never be completely actualized).

For an example of this trend many recent, popular pieces of art and cinema have likely drawn their inspiration directly from Tissot's vision. Perhaps most recognizable instance is the design of the Hebrew Ark of the Covenant used for the movie Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Another instance might be the similarity of many Life of Christ scenes to artist Harry Anderson's paintings for the Church of Latter Day Saints (1960s), images familiar to Mormons around the globe for their frequent use as illustrations in Mormon religious texts. Other films that have been credited for referencing Tissot include "From the Manger to the Cross (1912), William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959), and Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth (1977)" (Nicholson).

Though Tissot's Life of Christ series has become at best a distant memory for today's world, it may still be the most widely influential work of his career. Considering the dramatic shift in style that Tissot brought to the genre of biblical artistry and the widespread promulgation of his paintings in the form of family Bibles, Tissot's recovered vision of Holy Land doubtlessly left an unconscious impression upon an entire generation's mental image of the Holy Land, informing their imaginations with the vocabulary of his geography, clothes, peoples, and architecture. Even if Tissot's name and his Life of Christ series are themselves now unknown to contemporary men and women, the quintessential Holy Land characteristics which society expects in every movie, Biblical illustration, and nativity set are all likely the result of the devotions and labors of a certain James Joseph Tissot .

Now Experience the Works Yourself!

After touring Europe and America to great success, the entirety of Tissot's Life of Christ series was purchased by the Brooklyn Museum in 1900, where they have stayed ever since. Alongside the 340+ gouache color paintings that make up the primary body of this series, Tissot also included over a hundred pen and ink contextual drawings throughout his Gospel publication. These too have been preserved as part of the Brooklyn Museum's collection.

The presentation or gallery linked at both the top and bottom of this article is organized with the full color paintings first. They are divided into the major sections given in Tissot's Gospel and generally follow the chronology given in Dolkhart's The Life of Christ and Tissot's original publication. Next are as many of the supplementary illustrations as could be located, organized by subject category. Further reading and instructions on how to locate original files for most of these works is listed below.

The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ

The Holy Childhood (Slide 3)

The Ministry (Slide 35)

Holy Week (Slide 183)

The Passion (Slide 214)

The Resurrection (Slide 320)

Supplemental Content (Slide 357)

The Old Testament

Full Painting Gallery

Update as of 30 May 2023: I hope to complete this, but I have been delayed due to a busyier phase of life. Let me know if this is something you would enjoy seeing!

Update as of 16 August 2023: My Google Slides presentation was briefly unavailable due to a change in Google Drive accounts. The updated presentation should now be available and is linked in this article.

Note about the links below: none of my work would have been possible without the incredible resources and photographs provided by the Brooklyn Museum and their beautiful book on The Life of Christ by Judith M. Dolkhart. I have linked their works below alongside some other helpful resources such as Catholic-resources' directory of images and Lucy Paquette's blog, The Hammock, containing countless articles about Tissot's fascinating biography. I have also added a link to a page where you may view the 4 volumes of Tissot's English Gospel, including a signature inside the front cover of Vol. 1 likely dedicated to William Gladstone, famous Prime Minister of the UK.

Further Exciting Content Relating to The Life of Christ:

Digital copy of Tissot's original Life of Christ for American Audiences

James Tissot: The Life of Christ by Judith M. Dolkhart (ISBN: 978-1858944968)

thehammocknovel.wordpress.com Fascinating articles and a novel based on James Tissot's life.

James Tissot: Fashion and Faith, Closing Weekend Symposium Lecture Pt. 1 and Pt.2

To locate the details and high resolution images for any painting, consult the Brooklyn Museum's website: simply search the title of the painting alongside the phrase "Brooklyn Museum Tissot" on Google or search directly on the museum website (though I experienced mixed results with the museum website's search).

Catholic-resources.org Near-complete directory of Tissot's Life of Christ paintings, but low-quality images.

Citations and Sources:

Bailey, Albert Edward, 1871-1951. The Gospel In Art. Boston: Pilgrim Press, 1916.

The Brooklyn Museum, www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/search?keyword=tissot. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

Carrigan, Margaret. "James Tissot: the 19th century painter who swapped high society for the Holy Land." The Art Newspaper, 9 Oct 2019.

"Death of M. James Tissot." Evening Mail, 11 Aug 1902.

Dolkhart, Judith, ed. James Tissot The Life of Christ. London, Merrell Publishers, 2009.

Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D. "Gospel Illustrations by James Tissot." Catholic Resources, https://catholic-resources.org/Art/Tissot.htm.

Garber, Zev. "That Jesus Cover." Shofar Vol. 30 No. 3, Spring 2012, pp. 121-141.

H.V. de S. "Departure of the prodigal son/Return of the prodigal son." Le Petit Palais, www.petitpalais.paris.fr/en/oeuvre/departure-prodigal-sonreturn-prodigal-son#:~:text=Tissot%20portrays%20the%20parable%20of,eras%20was%20not%20universally%20popular.hl=en&lr=&id=P6mEQxvFvaMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA15&dq=james+tissot&ots=jTBcJe9Xc_&sig=6xfLrGgj5GHrbwBFVPyH_CYwbzo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=james%20tissot&f=false.

"James Tissot: Fashion, Faith and a Life of Passion." Juxtapoz, 12 Nov 2019.

Kleinschmidt, Beda. "James Tissot." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 27 Oct. 2020 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14741a.htm>.

Levy, Clifton Harby. "The Life of Jesus as Illustrated by J. James Tissot." The Journal of Religion Vol. 13 No. 2, Feb 1899, pp. 69-78.

Misfeldt, Willard E., James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bio-Critical Study, Ph.D. diss., 1971,Washington University, Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International.

Moffett, Cleveland. "James Tissot's Pictures of the Life of Christ." The Windsor Magazine Vol. 11, Dec 1899, pp. 3-16.

Muchmore, M. "Story of the Nazarene.: The Life of Christ as Told in the Paintings of J. James Tissot." Detroit Free Press (1858-1922), 25 Dec 1898, p. C3.

Nicholson, Louise. "From the high life to the Life of Christ – James Tissot’s path to piety." Apollo Magazine, 3 Dec 2019.

Paquette, Lucy. "A James Tissot Chronology." Victorian Web, www.victorianweb.org/painting/tissot/chronology.html. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot: Portraits of the Artist.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2017/08/15/james-tissot-portraits-of-the-artist/. <30 Oct 2020.>

Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot, the painter art critics still love to hate: a retrospective review round-up.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2020/01/15/james-tissot-the-painter-art-critics-still-love-to-hate-a-retrospective-review-round-up/. <29 Oct 2020>.

Paquette, Lucy. “Portrait of the Pilgrim: James Tissot’s Reinvention (1885-1895).” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2019/02/14/portrait-of-the-pilgrim-james-tissots-reinvention-1885-1895/. <29 Oct 2020.>

Paquette, Lucy. “Tissot’s La Femme à Paris series.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/12/20/tissots-la-femme-a-paris-series/. <29 Oct 2020.>

Perrin, Paul. "James Tissot: Fashion and Faith | Closing Weekend Symposium Pt. 2." Youtube, uploaded by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 3 Apr 2020, https://youtu.be/jTJ60uDnw3s?t=4422.

Sherard, Robert H. "James Tissot and His 'Life of Christ.'" The Magazine of Art, Jan 1895, pp. 1-8.

Wentworth, Michael. James Tissot. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 8 Mar 1984.

![Troisième frontispiece [Ten Etchings by JJ Tissot], Tissot 1876. Public domain image from the Bibliothèque National de France.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cf64e2_1b49e7c747f645eaac55ee83f74bd852~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_178,h_250,al_c,q_30,blur_30/cf64e2_1b49e7c747f645eaac55ee83f74bd852~mv2.jpeg)

![Troisième frontispiece [Ten Etchings by JJ Tissot], Tissot 1876. Public domain image from the Bibliothèque National de France.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cf64e2_1b49e7c747f645eaac55ee83f74bd852~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_394,h_553,al_c,q_90/cf64e2_1b49e7c747f645eaac55ee83f74bd852~mv2.jpeg)

Thank you for this. Is there a link to the Old Testament paintings still available?

I love this. Thank you. I have been researching and writing about Tissot and his Life of Christ illustrations for about four years. I admire what you are doing! Tissot is great! Here is one article I published at Religion Unplugged. Contrasting Visions Of Painter James Tissot, The Secular And Sometime Mystical Realist: https://religionunplugged.com/news/2023/1/29/contrasting-visions-of-painter-james-tissot-secular-and-sometime-mystical-realist (from another avid Tissot admirer)

Thank you for the work you have done compiling Tissot's Life of Christ! I would look forward to seeing the Old Testament collection as well, once you have time to complete it. It's a shame that these paintings are no longer in print. They could be used as an excellent illustrated Bible.